The Line Between Chaos and Harmony: An Interview with Film Photographer Cato Lein

1 7 Share TweetCato Lein wants his images to be "in the bebop" of photography. Somewhere "in-between", not quite comfortable, deliberately dissonant, like the feeling of swelling anticipation. His photography career gained traction when he began photographing writers for Swedish publications on Polaroid 665 film; up until now he has photographed fifteen Nobel Prize winners in literature. He shoots with large-format cameras as casually as with a point-and-shoot, embraces happy accidents, and keeps his curiosity always burning.

In this interview Cato Lein talks to us about his ongoing project, a photo book called The Poet and the Baltic Sea, which he was inspired to create after spending time with the renowned Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer. Tranströmer and his work linger "like a shadow" beneath the surface of this project, guiding Lein along each coastline touched by the Baltic Sea.

Hi Cato, could you start by telling us a bit about yourself and how you started with analogue photography?

Yes. First, I’m from Norway, and came to Stockholm in the 80s. And in those days it was only analogue. I went to Stockholm because they didn’t have any high schools for photography in Norway at that time […] I’m from a small fishing village in the north of Norway, so I wanted to go to a big city.

After I had been working as a printer for 4 or 5 years I started testing myself as a photographer, and directly I got a job at Dagens Nyheter and Göteborgsposten. They bought all my pictures of writers; I was working for the [culture section] at those places. They gave me names of authors and filmmakers and musicians - Paul Auster, Susan Sontag, and Nobel Prize winners in literature. So after a year or two, I had a great archive with these photos. I started taking portraits with [large format] sheet film cameras - 4x5’’ and Polaroid film. In those days, Polaroid was a negative and a positive, so I could work with the negative in the darkroom and make a nice print.

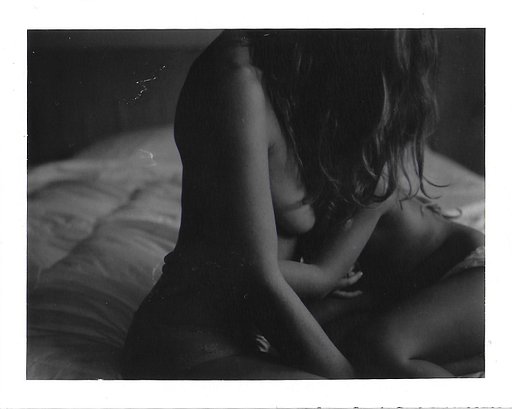

I’ve never been a technical photographer, [I work] more with feelings, and intuition. So, I didn’t know, but, in a way, I started a new way of taking pictures. When I was working with a big magazine, my pictures were directly accepted, [because] I had a new way of working. It was like I was taking point-and-shoot [photographs] with big, wooden cameras. I mean, I didn’t care if the picture was a little out of focus or [the person] was moving. It was more the feeling of it - the eyes, the sight of the person.

You’ve used a real variety of different films and cameras: a Holga, a large-format camera, Polaroid 665, which you mentioned. How do you go about choosing which to shoot with, and what are the challenges and rewards of these photographic processes?

The person you’re taking a picture of is very curious when you come with a plastic Holga camera, they think I’m joking! It’s not a dangerous camera. This is much better than coming with a Canon EOS, you know. It’s easier to get a nice pose, because there is no reaction. If I take a portrait with a Linhof, it’s got a tripod and everything, they think that's a very strange camera as well, because I go under the sheet and find the focus, and it takes time, and then the picture is over! And they go, wow, that’s it, only one picture.

You really manage to capture these boundary-less moments between you, the subject and the viewer. How do you create this environment where the people you photograph are so prepared to open themselves to the camera?

It’s the way you talk to them. With writers, [they are all] curious, they are storytellers. I love to talk with people, and, for me, [it’s] not the big name “Susan Sontag”, it’s just an ordinary woman who wants to have her picture taken from the left or from the right - they have their own way of doing this and that.

Like John Irving. I met him when I was going to take a portrait of him in Stockholm, and after he signed his book and I was going to take a picture, [I saw] he had flip-flops and shorts and an Adidas t-shirt on. I thought, my God, how can I take a picture of this? He was walking on the street on the way to the hotel and I said to him - because I know that he had been a sportsman, a wrestler - I thought about the movie Taxi Driver. There is a scene with Harvey Keitel, he’s a pimp for Jodie Foster, she’s working as a prostitute. And Robert de Niro comes with a weapon, he wants to destroy this guy, and he’s standing like this, with his arms [crossed], in the doorway. And I said to John Irving, I want you to be like Harvey Keitel, standing in the darkness in the background, just standing there. “Ah, that’s a nice idea!” [he said]. Very close to the hotel, I found this little dark doorstep and he stood there, and I just took two pictures, said “thank you, bye bye, good luck with your book!” And it was really a good picture - but a very ordinary picture.

When you do portraits, you can very easily read what kind of person he is or she is […] with the way he is standing. [The most important thing] when you take a portrait is that you make them relax. That’s why I talk very much, even too much, to make them confused!

I learned something from Richard Avedon, I learned from the way he could tell the person a story. It could be a very sad story, of a dog he had, and he knew that the people [who he was photographing] loved dogs, and he talked about a traffic accident; he lost his dog because a car killed it. And he was saying this to the couple, and they nearly started crying, and then he took the picture. He got this sadness in their eyes. And for me, that’s very interesting. I don’t like sadness in pictures, but I don’t like teeth or too much smiling. I love if there is a smile, but more if there is an explosion of smiles, when they are laughing in a natural way. But not smiling like it’s a photo for a job.

So I have my little techniques. It’s small details, but it’s very important to learn them. I have that feeling in my bones, of how to break the ice, of getting closer to the person.

Do you think this kind of storytelling while you’re taking someone’s portrait drew you to photograph writers and artists? You have a big collection of photographs of authors and poets - what is it that drew you to that world?

Today, I have [photographed] fifteen Nobel Prize winners in literature. I’ve been lucky, and magazines hope that I can take a “new” picture of this person, that it’s not this ordinary, detailed picture that is everywhere in the magazines, where they are just standing there. Okay, in my pictures they are standing, or sitting. But I try to find some nerve in their eyes, in their way of sitting or standing. You have to be like a psychologist, one step ahead, and you can read their next move, in a way. You feel that soon you will have the picture. And - there it is, and you have it!

It’s interesting that you say that, because Tomas Tranströmer was a psychologist in his early career and when I saw this series of yours I felt that his poetry and your photography had something similar about them. Something heavy, but also meditative. What do you think about that?

I was visiting Monica Tranströmer last weekend, and she was very surprised when she saw the pictures, because she understands what I’m looking for, but she didn’t know that I’m a sort of landscape photographer. She [had just] noticed that I’m an author photographer for publishing houses and so on. I told her how I was thinking: Tomas Tranströmer worked very much from pictures, or a feeling he got when he was getting close to a church, or in an open field, or if there was a storm coming. He [writes] in a very simple way, but it’s always a metaphor for something else, something much bigger. And that gave me a sort of freedom to choose my own language based on his poetry. Because he was basing his own text on another picture, a long way before me.

Could you tell us a bit more about the origin and context of this project, The Poet and the Baltic Sea?

It began when Monica called me - I know one of their daughters - and they asked me to come to the house because an American translator was visiting, Robert Bly. So she asked if I could come and take some pictures of Tomas and Robert. I live not far from there, it’s only [a ten minute walk]. So I did, and then I started working with them, visiting them very often. Sometimes I didn’t take pictures. But I was very often in the archipelago.

There are days when the Baltic Sea is a still, endless roof.

So then dream naïvely about something crawling on the roof that

tries to untangle the flaglines,

try to raise

the rag-

the flag that is so weathered by the wind and smoked by the chimneys and

bleached by the sun that it could be everyone's.

But it is a long way to Liepāja.

- from Östersjöar, Tomas Tranströmer, translated by Emilie Jung-Andersson

I was a sort of friend to the Tranströmer family, and I used to visit them in their summer house, out in the Baltic sea […] I was working with him until the end, let’s say. I didn’t want to do this sort of portrait book about Tranströmer, I wanted to do a traveling book [based on] his long poem, ‘Östersjöar’. It came out in ‘74. I thought that it was a very good start for this book. It’s about a grandfather, he was a marine pilot, lots is the Swedish word. They help foreign boats to come into Stockholm. They needed locals on the big ships so they could find their way to the port, because there are a lot of small islands [in Stockholm], and they knew where to go. And Tomas Tranströmer’s grandfather was a marine pilot, he always used to write notes about the ships - how tall they were, the names and everything. And I thought, this is a very good start for my book.

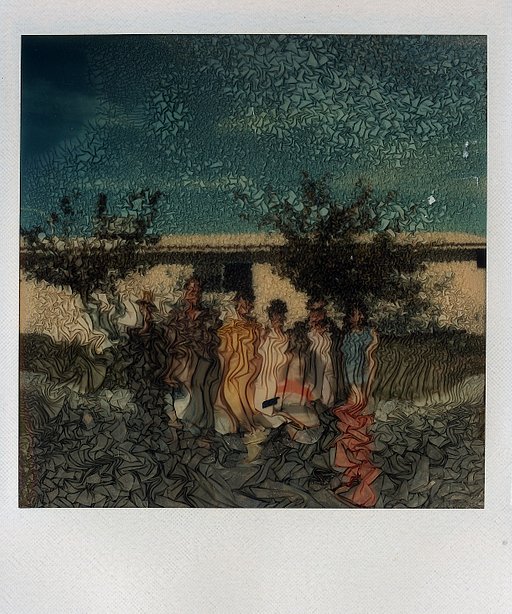

This will be a book about the Baltic sea, not about Tomas Tranströmer, but Tomas is like a shadow, he is guiding me. There is some great poetry from the Baltic states, from Lithuania […] He was translating a lot of poems from the Baltic states to Swedish. So he has a lot of friends over there […] After the pandemic time I went to Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia. I got a very good collection of pictures from this area. And then I went for fourteen days to Ingmar Bergman’s home in Gotland, in Fårö, collecting pictures there and putting them all together for the book. So now I’m doing the final selection.

There’s a photograph in this series where Tranströmer appears headless, his face melts into the background. Was this intentional? If not, how do you approach “accidents” in your work?

A very nice accident. I don’t think so much about making mistakes, mistakes come to you. That’s why I like analogue cameras - like the Holga. I use the Holga [120 Pan] with a Linhof lens. The Holga lens is plastic, and it’s a little bit too soft for me. But I like its style, it leaks light, and it’s easy for something to go wrong. A lot of those things, I can use. Sometimes it’s really a catastrophe, but sometimes there can be a very nice leak.

For my work with publishing houses, and jobs that get me food for the next month, I only do digital. With digital it’s very easy to get the perfect pictures. And I think it’s great, but I don’t like that so much personally, it’s not my language. I’m not a technical photographer. I want to see what happens, I’m a curious photographer, and I love when something goes wrong, when there is some leaking or some double exposure, or something surprises me. I get a kick out of that. But with the digital cameras I never get a kick, it’s just… it’s so boring, sitting there taking pictures! I’m a little color blind as well, so I don’t work so much with color. When I do take color pictures I put it on automatic and put some nice filters on it!

Is that one of the reasons why you only shoot black and white?

I grew up with black and white pictures. I like high fashion photographers like Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, Anton Corbijn. I also like Robert Frank and Moriyama, who take hundreds of pictures every day. They just see something and [shoot] - I love that kind of shit! And I like the [contrast] of super intellectual photos with a point-and-shoot.

I study literature, and the way you talk about photography is really similar to the way we talk about literature - if you have a complicated message in your writing, you need to use simple language, and if you have a simple message it’s ok to use complicated language. It makes more and more sense why your work and Tranströmer’s feel so similar. Do you see photography as a language?

Yeah, for sure. It’s a great language! For me, I like it when people are saying, “that picture feels dirty, I don’t feel well with that person’s personality.” Then there is a reaction, and I like that. Or they feel, “this is really great, this is like a picture from the American Great Depression time,” or something like that. For me it’s important that there is a feeling for those who are looking at my pictures. And that’s an international language, I think. It’s like music, it’s like piano. Wherever you are from, you can like the music. And you can also not like the music.

I’m Norwegian but I really like the Swedish melancholy mood, vemod, we call it. I like to have my pictures in that mood as well […] something in between. Not too perfect. Music can sound a little false, like something is going wrong, but it’s on the line between chaos and harmony. Atonal music, you know. [That is where] I want my pictures to be. Like bebop in jazz music. It sounds like a tractor driving, and you’re just waiting for the tractor to fall off the cliff, but they keep it there. Like Miles Davis’s music. There I want to be. In the bebop.

Do you have any projects coming up aside from this one?

I want to do more slideshows. Everywhere I go, I want to [make] a project out of it. Just a little project. I was in the south of France, I was invited to a photo festival in Sète, close to Montpellier. And I saw this film about Agnès Varda, she was a film director from Sète. And suddenly, when I saw her short films, I thought, wow! I was walking there and taking pictures, and now I want to do a little slideshow around Agnès. She did her films in the 50s but it was very similar to Bergman’s Persona - people are walking and they don’t talk so much, very typical of French movies from the 50s and 60s. So after I have finished collecting pictures I will do more slideshows, with some music […] I’m rather old now, but I’m still very curious.

Where does that curiosity and inspiration come from?

Music, movies, outside. There is inspiration if you want to see it. During the pandemic time, it was terrible because everything was locked down. So I was walking in the woods, in the forest, and taking pictures of trees that had fallen down, just to see. Like a piano player who plays every day to keep the fingers soft. It’s the same with a camera, you have to practice pressing the shutter.

We'd like to thank Cato for sharing his work and insights with us! To view more of his work, follow him on Instagram and check out his website.

Discover more of Tomas Tranströmer's poetry!

written by emiliee on 2023-12-04 #people #videos #in-depth #landscape #sweden #portrait #norway #poetry #literature #scandinavia #baltic #cato-lein #tomas-transtromer #the-poet-and-the-baltic-sea

One Comment